This case study discusses a Participatory Design pilot project at Montana State University: User Experience with Underrepresented Populations (UXUP), in which Native American students and a librarian co-created a new community outreach tool. It provides an in-depth view into the UXUP design process, with further discussion of outcomes, limitations, assessments, and recommendations for implementing Participatory Design practices with Indigenous communities.

By Scott Young, User Experience & Assessment Librarian at Montana State University (August 2018)

Introduction

How can we ensure that Native American students are welcomed and empowered on campus? Participatory Design offers one answer to this question. Participatory Design is a socially-active, politically-conscious, values-driven approach to co-creation that seeks to give voice to those who have been traditionally unheard. This case study discusses a Participatory Design pilot project at Montana State University: User Experience with Underrepresented Populations (UXUP), in which Native American students and a librarian co-created a new community outreach tool. This case study provides an in-depth view into the UXUP design process, with further discussion of outcomes, limitations, assessments, and recommendations for implementing Participatory Design practices with Indigenous communities. The UXUP project can serve as a model for empathetic and collaborative design, with the ultimate outcome of creating more inclusive library experiences for all users.

Problem and Context

In 2015, Sumana Harihareswara wrote an article published in the Code4Lib Journal entitled, “User Experience is a Social Justice Issue,” in which she encourages a disciplined empathy in the work of designing library services in order to achieve social justice goals and implement human rights (Harihareswara, 2015). In calling for more empathetic approaches to library user experience and service design, Harihareswara motivated a new initiative at the Montana State University (MSU) Library: User Experience with Underrepresented Populations (UXUP). The primary goal of the UXUP project was to better understand, empathize with, and empower Native American students. To achieve this goal, we followed the methodology of Participatory Design, a socially-active, politically-conscious, values-driven approach to co-creation that seeks to give voice to those who have been traditionally unheard (Ehn, 1993; Robertson & Simonsen, 2013).

Participatory Design begins with the idea that the user and the designer each possess skills and perspectives of equal worth. This equity is realized through a practice of mutual learning, power sharing, and decision making among the participants. For the UXUP project, the MSU Library worked with our Native American community to develop a Participatory Design practice anchored by a Native American student group empowered to share their experiences in their own voice, and to co-determine the direction of the design process. UXUP aimed for both practical and political outcomes: practically, UXUP aimed to create better user experiences for our campus’ Native American student population; politically, UXUP aimed to create new space and structures for Native voices to be empowered in the decision-making process of the library, with the goal of improving the conditions for Native students.

The motivation for UXUP is also derived from existing institutional commitments from Montana State University (MSU), the state’s land-grant university. The land now known as Montana is home to many communities of Indigenous peoples, including the Blackfeet, Chippewa-Cree, Salish and Kootenai, Crow, Assiniboine, A’aninin, Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and the Little Shell Chippewa. Native American students from these Nations and others in the region represent about 4% of our student body—about 700 students. In support of our Native students, the MSU Office of the Provost sponsors a Native American Recruitment and Retention grant program, which annually funds projects that focus on Native American student success. UXUP was developed as a response to this grant call, and was awarded $7,200. Grant expenditure included compensation for participants, project supplies, and travel for presenting the project at the 2017 Code4Lib Conference in Los Angeles and the 2017 American Indian Heritage Day in Bozeman, MT.

UXUP therefore builds on a foundation of institutional support, Participatory Design theory and practice, and social justice through a lens of decolonization and Indigenous self-determination. Ultimately, the UXUP project can serve as a model for empathetic and collaborative design research with Indigenous communities. This case study is told from the perspective of a non-Native librarian of European ancestry, and is intended for a non-Native reader. It presents an overview of the process, products, and limitations of the UXUP project.

Descriptive analysis

The UXUP project took place from January 2016 to August 2017. The first year was comprised mostly of relationship-building, literature review, and project planning. I met with Native leaders on my campus to better understand the viewpoints, values, needs, and strengths of Native students. I also reviewed and studied the literature of Participatory Design, Critical Race Theory, and Indigenous Research Methodologies, and began to plan UXUP with the assistance of a Native student co-leader. The centerpiece of the project involved a semester-long design workshop series involving four Native students and me. In December 2016, we convened the first workshop, and the series continued with twice-a-week, hour-long workshops from January 2017 through April 2017. The project concluded in August 2017 with the creation of the final design products.

The design workshops formed the most important space and structure for the project. During this time as a small community, we strove to realize the Participatory Design principles of mutual learning, equal expertise, and shared power. The group met twice a week for 4 months. Each hour-long session focused on one or two design exercises. The exercises provided a structure for creative thinking that allowed the participants to share their experiences as Native students, identify common issues, and co-create a response to the most critical issues surfaced. The design workshops took place in the library’s Innovative Learning Studio, a flexible, technology-enhanced learning space. In addition to providing a physical space for creative thinking and storytelling, the open-ended, Native-centered mindspace of the design workshops allowed Native values and strengths to come forward and flourish in a such a way that the participants were able to express their own conceptions about who they are, their relationships with Native and Non-native people and institutions, and the land on which we lived and worked.

UXUP was informed by the theories of Participatory Design, Critical Race Theory, and Indigenous Research Methodologies (please see Bibliography for additional readings). The practice of UXUP was informed and guided by the exercises outlined in the following set of design tools: 75 Tools for Creative Thinking; Gamestorming; Intuiti Creative Cards. With a theoretical grounding and practical tools at our disposal, we followed a three-stage design approach:

- Stage 1: Topic Investigation — discussing topics, concepts, and problems related to the general life experience of participants

- Exercises

- Interviews

- Intuiti Creative Cards

- Great Pie

- The Time Machine

- Mindmap

- Build Your Vehicle

- Exercises

- Stage 2: Idea Generation — generating ideas and potential solutions around key topics explored in Stage 1

- Exercises

- Predict Next Year’s Headlines

- Collage

- Journey Map

- Value Curve

- Clockwise

- Exercises

- Stage 3: Evaluation and Implementation — evaluating and implementing the most desirable, feasible, and viable solutions generated in Stage 2

- Exercises

- Club Members

- Smiley Voting

- Paper Prototyping

- Storyboarding

- Final design creation

- Exercises

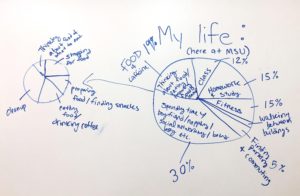

A full description of the UXUP process is beyond the scope of this case study, but I can discuss highlights from each stage to illustrate our progression. At Stage 1, we began with getting-to-know-you exercises that focused on the participants’ life and background, with the intention of building trust and rapport within the group. For example, The Great Pie (Figure 1) asked participants to represent their life in the form of a pie, with different slices showing the percentage of time dedicated for various activities.

Low-stakes, easy-to-complete exercises such as this serve the purpose of introduced participants to each other and also to the creative process of participatory design.

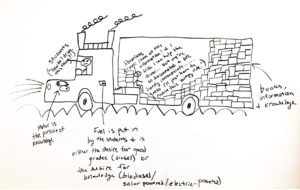

From there, participants were asked to represent and discuss their interactions with the library. The Build Your Vehicle exercise (Figure 2), for instance, allowed us to identify a key issue relating to the experience of Native students in the library: a sense of intimidation and uncertainty in entering a new, unfamiliar, white-dominated space.

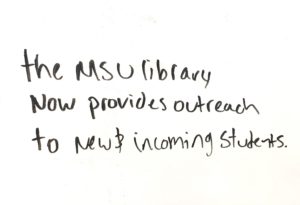

With this key insight, we transitioned into Stage 2, and began to generate ideas for responding to and addressing this issue. To structure our thinking at this stage, we completed the exercise Predict Next Year’s headlines, where participants were asked to think into the future and imagine an ideal outcome of the project. One participant imagined a new outreach mechanism for Native students (Figure 3).

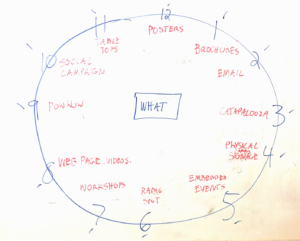

In follow-up discussions, the participants identified promise in this idea, so we completed a subsequent exercise intended to bring more clarity and detail to this high-level idea. This exercise—Clockwise—asked participants to propose different ideas in response to a prompt, then remixed the ideas together in order to form new connections and new ideas. In our case, the prompt involved a new outreach service for Native students, and the group produced 12 different possibilities (Figure 4).

These 12 ideas were then randomly remixed via a dice roll, producing a new set of possibilities for the group to discuss and critique (Figure 5).

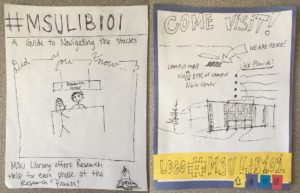

In follow-up discussions, the group identified a poster series and social media campaign as the most promising methods for reaching out to Native students. This finally led to Stage 3, where we refined this idea and produced the final design product. The group produced storyboards (Figure 6) and paper prototypes (Figure 7), leading ultimately to a final poster design, which was designed using the free online tool Canva (Figure 8).

Throughout this process, the participants and I worked together as a group to discuss the design evidence that was produced in each session, and we discussed and decided together how to proceed in terms of the timeline and the exercises. Over the course of the project, the students became more confident library users, and their voice played an essential role in moving the process forward to the final product. Together we co-created a new community-building outreach tool meant to address a real issue for Native students identified by the participants themselves.

Outcomes

The UXUP project produced two outcomes: a practical design product that helps Native students feel more comfortable and capable in entering and navigating the library, and a political outcome focused on decolonizing library practice and research through critical self-awareness and the empowerment of Indigenous participants.

The first outcome of UXUP was the practical design product itself. The UXUP group co-created a promotional poster series and social media campaign that highlights key library activities for Native American students, called “#MSULib101: A Guide To Navigating Your Library.” (please see the final poster designs: http://www.lib.montana.edu/about/msulib101/). The new community-building outreach tool has been placed in strategic locations around campus, including dining halls, residence halls, and places where Native students gather, such as our American Indian Center (Figure 9). The posters feature the project participants themselves. Accurately representing Native students engaged in library activities is a small but essential step forward for serving this student population.

For the Native student participants, an increased sense of belonging and skill was developed over the course of UXUP. Following the conclusion of the project, students continued to visit the library and use library services with greater frequency and ease. This assessment was conducted through informal conversations with participants. In follow-up correspondence after the project ended, for example, one participant expressed that “it was a joy working with everyone and to be able to be part of this amazing project.” This comment also represents the important social bonding and community building that occurred among the participants. From my perspective as a non-Native librarian, I also gained a deeper understanding of and empathy towards the needs and strengths of my university’s Native population. The trust relationships developed with the participants and with Indigenous leaders across campus is a crucial outcome in itself, as it will allow our library to advance social justice goals with Native peoples as partners.

This leads to the political outcomes for the project. UXUP is driven by a focus on power relations and a sense of social and racial justice. Native American students are often at the margins of university politics due to dominant social paradigms that have traditionally undervalued Indigenous life. With this in mind, the main political outcome of UXUP was the amplification of Native voices, with a decolonizing view towards improving the material conditions of Native students. Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012, p. 201) writes that the decolonizing activist works “to defend, protect, enable, and facilitate the self-determination of Indigenous peoples over themselves in the states and in the global arena where they have little power.” And that such global activism “begins at home, locally.” In our case, we worked locally at our university to enact change and improve our library for our Native student population. Through the UXUP project, participants were empowered as self-determining storytellers to share their experiences and co-create a new library service in support of the university’s Native student population.

The political aim of UXUP works in support of a larger, more radical vision, that of a decolonized world. Decolonization is about self-determination and control, where Native peoples exist free from an oppressive and exploitative settler colonial state (Tuck & Yang, 2012). An Indigenous future of this kind is a world of personal and tribal sovereignty, where the rights of the Indigenous are respected and ancestral knowledges serve as a guide (Roanhorse, 2018). In its small-scale way, the UXUP project attempted to create an Indigenized space that centered Native values, viewpoints, strengths, and needs.

While the UXUP project made some steps forward, the process was flawed. Most critically, the project over-considered the Scandinavian tradition of Participatory Design and under-considered Indigenous research methodologies and epistemologies. Though we aspired to Indigenization, such a goal is not fully achievable with a design process shaped by a Western paradigm. I consider this a significant misstep, and one that I only grasped partway through the project, as I was less familiar with Indigenous knowledges and inquiries at the time of the initial project design. I was also less aware of my own bias, power, and privilege at the beginning of the project. This produced blind spots that focused my attention too much on Participatory Design at the expense of Indigenous researchers and practitioners working in adjacent spaces. For those coming from places of privilege, doing social justice work will likely result in mistakes along the way. April Hathcock offers invaluable guidance in her blog post “You’re Gonna Screw Up.” Hathcock notes, “Many white people pretend to be serious about anti-racism yet ghost the minute things get tough…but if you’re really serious about doing this work, you will take the initiative and learn from your mistakes.” Indeed, learning and growing with sincere self-awareness is essential to move this work forward. As a non-Native person who inherently benefits from systems of oppression and privilege, arriving at a sense of my own power and its effects is essential for growth and justice. Through UXUP, I have learned that from a place of critical awareness of self and system, I can begin to apply my power not in service to itself, but rather to increase the power of others.

Next Steps and Research Agenda

UXUP has ended, but the spirit of the project will continue to develop as relationships with Native students and leaders are sustained and deepened, and as my own understanding of Indigenous research methodologies continues to grow. So the next steps for UXUP are to further research and practice around decolonization and Indigenization, with greater and more meaningful power sharing and participation with traditionally oppressed Indigenous peoples through a thoughtful integration of Indigenous research methodologies and Participatory Design. Margaret Kovach, an education researcher of Plains Cree and Saulteaux ancestry, concisely articulates the importance of participation for Native peoples, “the power lies with the research participant, the storyteller.” (2010, p. 125). In this way, Participatory Design and Indigenous methodologies find a common ground. With a focus on shared power and co-creative participation, both approaches seek to address historical imbalances of power and participation. Through creative thinking exercises, Participatory Design provides space and structure for participants to tell the story of their experience in their own voice and in a space safe for open expression.

In this pursuit, I and other non-Native practitioners need to be respectful and thoughtful towards Indigenous peoples, to approach the work with cultural specificity and sensitivity, and to acknowledge the history of exploitative research that makes work in this space fraught and challenging (Kovach, 2010, p. 125). We are embedded within the same structures of power that Participatory Design and decolonization projects seek to challenge. Through an interrogation of self and system, we provide space to challenge ourselves and others in our profession to more strongly address oppression and work towards justice. To do so effectively, we can engage with Indigenous people on our campuses and within our communities: attend gatherings, listen, and learn the experiences and knowledges of the people we seek to collaborate with.

Ultimately, UXUP can be adapted and reapplied to better serve and empower Native students at other institutions. But this approach of activist Participatory Design is not without its challenges and barriers, which are also both practical and political.

From a practical perspective, the process of participation takes time and resources (Gaudio, Franzato, & Oliveira, 2017). For UXUP, the student participants were compensated at an attractive rate for their labor, and I was allowed the institutional support to build in this direction. For those who wish to follow the principles and practices of UXUP but who have less available resources, I would recommend finding allies and cultivating relationships with others who share similar goals. Collaborations across departments or campus units can help boost the profile and secure funding. There may also be strategic inroads with diversity-related funding initiatives from universities, professional associations, and other organizations that provide resources for projects that support underrepresented groups. If funding and time remain elusive, a project such as UXUP could proceed as a skunkworks pilot project, with the goal of demonstrating small successes so that funding could eventually be secured from library or university administration. Participatory Design can also be challenging to assess (Bossen, Dindler, & Iversen, 2016). Assessment of UXUP was approached through informal self-evaluations follow-up interviews with participants. More formal assessments might strengthen the outcomes of Participatory Design projects, and could also bolster justifications for additional resources.

From a political perspective, entrenched power structures present obstacles not only to participation generally, but Indigenous justice specifically. Practitioners who wish to extend this work should maintain a careful attunement to power dynamics—Who is driving the process? Who benefits from the project? Whose questions are being asked? A few additional guiding questions can help frame the pursuit of Indigenous participation and empowerment:

- How can we improve the conditions of marginalized, underrepresented, and oppressed peoples?

- How can we engage with and deconstruct dominant stories and oppressive power structures?

- As researchers, how can we engage more critically with the research process?

- As practitioners, how can we bring Native voices into our areas of practice, and how can we pursue collaborative work that addresses community-defined needs of Indigenous peoples?

Participatory Design posits that people have a right to influence their own world, and offers a framework for empowering the traditionally marginalized. The collaborative, community-based practice of Participatory Design can exist in complement to Indigenous methods and in support of Indigenous populations, with the ultimate aim of creating a more just world.

Bibliography

Participatory Design

Bossen, C., Dindler, C., & Iversen, O. S. (2016). Evaluation in Participatory Design: A Literature Survey. In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Full Papers – Volume 1 (pp. 151–160). New York, NY, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2940299.2940303

Ehn, P. (1993). Scandinavian Design: On Participation and Skill. In D. Schuler & A. Namioka (Eds.), Participatory Design: Principles and Practice (pp. 41–77). New York: CRC / Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

MacTavish, T., Marceau, M.-O., Optis, M., Shaw, K., Stephenson, P., & Wild, P. (2012). A participatory process for the design of housing for a First Nations Community. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 27(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9253-6

Robertson, T., & Simonsen, J. (2013). Participatory Design: An introduction. In J. Simonsen & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design (pp. 1–17). New York: Routledge.

Gaudio, C. D., Franzato, C., & Oliveira, A. J. de. (2017). The challenge of time in community-based participatory design. URBAN DESIGN International, 22(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-016-0017-5

Young, S. W. H., & Brownotter, C. (2017, March). Participatory User Experience Design with Underrepresented Populations: A Model for Disciplined Empathy. Presented at the Code4Lib Conference, Los Angeles, CA. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1210020

Young, S. W. H., & Brownotter. (2017, September). Decolonizing and Indigenizing the Academic Library: A Participatory Design Approach. Presented at the American Indian Heritage Day, Bozeman, MT. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1210024

Indigenous Research Methodologies

Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous Research Methodologies. Washington, DC: SAGE Publications.

Grande, S. (2015). Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kovach, M. (2010). Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lambert, L. Indigenous Research Paradigm: A Conceptual Model. Retrieved from https://www.americanindigenousresearchassociation.org/mission/spider-conceptual-framework/

Suina, M. (2017). Research is a Pebble in My Shoe. In Indigenous Innovations in Higher Education (pp. 83–100). SensePublishers, Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6351-014-1_5

Higher Education and Indigenous Populations

Burke, C., & Könings, K. D. (2016). Recovering lost histories of educational design: a case study in contemporary participatory strategies. Oxford Review of Education, 42(6), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2016.1232244

Stein, S. (2017). A colonial history of the higher education present: rethinking land-grant institutions through processes of accumulation and relations of conquest. Critical Studies in Education, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2017.1409646

Tachine, A. R., Cabrera, N. L., & Bird, E. Y. (2017). Home Away From Home: Native American Students’ Sense of Belonging During Their First Year in College. The Journal of Higher Education, 88(5), 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.1257322

Windchief, S., & Brown, B. (2017). Conceptualizing a mentoring program for American Indian/Alaska Native students in the STEM fields: a review of the literature. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 25(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2017.1364815

Decolonization and Social Justice

Bowers, J., Crowe, K., & Keeran, P. (2017). “If You Want the History of a White Man, You Go to the Library” : Critiquing Our Legacy, Addressing Our Library Collections Gaps. Collection Management, 42(3–4), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2017.1329104.

Harihareswara, S. (2015). User Experience is a Social Justice Issue. The Code4Lib Journal, (28). Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/10482.

Roanhorse, R. (2018, February). Postcards from the Apocalypse. Uncanny: A Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy, (20). Retrieved from https://uncannymagazine.com/article/postcards-from-the-apocalypse/.

Simpson, L. B. (2017). As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (2nd Edition). London: Zed Books.

Print This Page

Print This Page